The researchers from the University of Surrey suggest that the Green Living Paint biocoating could be used in extreme environments such as space stations.

Scientists from the University of Surrey have recently presented Green Living Paint, an innovative biocoating containing oxygen-producing bacteria capable of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) that could be used in extreme environments such as space stations.

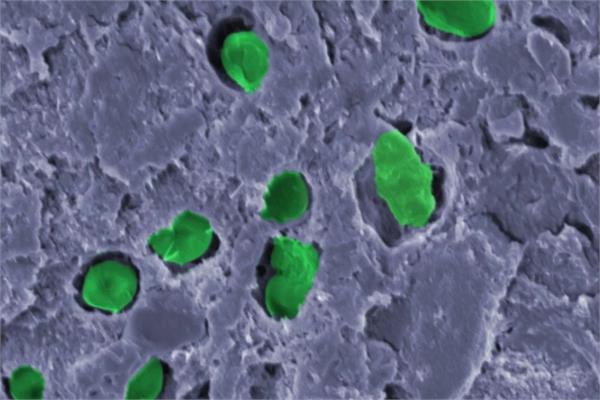

Biocoatings are a type of water-based paint that encase live bacteria

within their layers, which – besides capturing carbon dioxide – can also serve as bioreactors or as biosensors. Green Living Paint contains Chroococcidiopsis cubana, a bacterium that undergoes photosynthesis to produce oxygen while capturing CO2. It is usually found in the desert and requires little water for survival. As it is classified as an extremophile, it can then survive in extreme conditions.

“With the increase in greenhouse gases, particularly CO2, in the atmosphere and concerns about water shortages due to rising global temperatures, we need innovative, environmentally-friendly and sustainable materials. Mechanically robust, ready-to-use biocoatings, or ‘living paints’ could help meet these challenges by reducing water consumption in typically water-intensive bioreactor-based processes,” has stated Suzie Hingley-Wilson, a senior lecturer in bacteriology at the University of Surrey.

In order to investigate the suitability of Chroococcidiopsis cubana as a biocoating, the group of researchers immobilised the bacteria in a mechanically robust biocoating made from polymer particles in water, which was fully dried before rehydrating. They then observed that the bacteria produced up to 0.4 g of oxygen per gram of biomass per day and captured CO2. In addition, continuous measurements of oxygen showed no signs of decreasing activity over a month.

“The photosynthetic Chroococcidiopsis have an extraordinary ability to survive in extreme environments, like droughts and after high levels of UV radiation exposure. This makes them potential candidates for Mars colonisation,” has added Simone Krings, the lead author and a former postgraduate researcher in the Department of Microbial Sciences at the University of Surrey.

“Our research grant from the Leverhulme Trust enabled this interdisciplinary project. We envision our biocoatings contributing to a more sustainable future, aligning perfectly with the vision of our Institute for Sustainability, where both Dr Hingley-Wilson and I are fellows,” has concluded Joseph Keddie, a professor of soft matter physics in the School of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Surrey.