The news has gone around the world – the six-day strike called by the employees of SETE, the Eiffel Tower operating company, between 19 and 25 February has called attention to an issue that those working daily in contact with the world’s most famous Iron Lady say has never been so dramatic: the corrosion of its puddle iron beams.

How is it that such a common problem with metal surfaces had never been highlighted so blatantly and in such a high-risk structure as the Eiffel Tower? To understand this, we need to take a few steps back.

What is the origin of the Eiffel Tower?

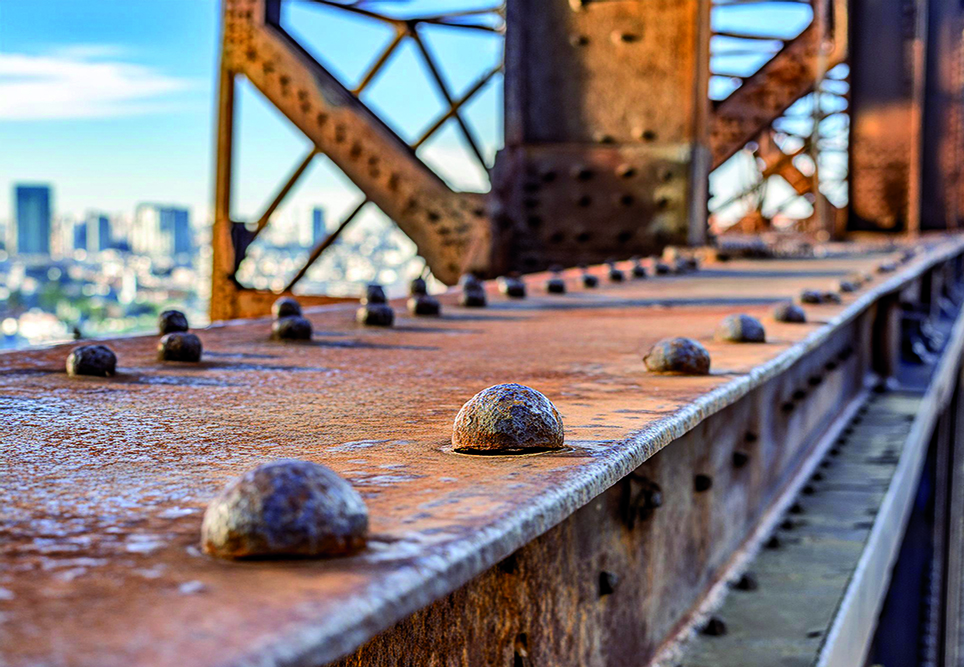

The Eiffel Tower is composed of 18,038 metal pieces and 2,500,000 rivets. © ipcm

The Eiffel Tower is composed of 18,038 metal pieces and 2,500,000 rivets. © ipcm

Standing at over 300 metres high, the Eiffel Tower has been rising over the rooftops of the French capital since 15 May 1889, when it was opened to the public for the Paris Exposition, two years after its foundations were laid. Presented by two engineers from the Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel, managed by Gustave Eiffel, one of the most respected “iron architects” of the time, this project had won the competition held to create a monumental work that was unique in the world and bound to become one of the capital’s most interesting sights, in the intentions of the French government that selected the winning design. It was to stand for twenty years, just long enough for Gustave Eiffel to recoup the costs of building the structure, which he financed largely out of his own pocket, but it soon became an irreplaceable symbol of the city.

Let us look at some of its construction features in detail:

- Workshop drawings: 5,300;

- Composition: 18,038 metal pieces and 2,500,000 rivets;

- Total weight: 10,000 tonnes;

- Metalwork weight: 7,300 tonnes;

- Total cost: 7,800,000 gold francs;

- Number of visitors: over 200 million since 1889;

- Number of steps: 1,665 from ground level;

- Pitch between the pillars at the base: 124.90 metres;

- Spacing between pillars: 72.25 metres;

- Width of the pillars: 26.08 metres.

The Iron Lady’s painting history

Since its foundation, the Tower’s 250,000 m2-wide surface has been repainted every seven years, with a total of 60 tonnes of paint applied in an operation that lasts an average of 16 months at an average total cost of 3 million Euros. Its official website states that “The repainting campaign is an important event in the life of the monument and takes on a truly mythical nature, as with everything linked to the Eiffel Tower. It represents the lasting quality of a work of art known all over the world, the colour of the monument that is symbolic of the Parisian cityscape, the technical prowess of painters unaffected by vertigo, and the importance of the methods implemented.”

Already at the time of its construction, Gustave Eiffel emphasised the importance of its paintwork: “We will most likely never realize the full importance of painting the Tower, that it is the essential element in the conservation of metal works, and the more meticulous the paint job, the longer the Tower shall endure. This consideration is of special importance for the Tower, due to the small volume of each of its components, their low thickness, and the exceptional weathering to which they were exposed.”

On average, therefore, the Iron Lady changes the colour of her “dress” every seven years. Venetian red was chosen for its first “dress”, applied directly in the Eiffel workshop in four coats of lead paint (minium), now banned but considered the best corrosion protection solution back then. Immediately after its inauguration for the Paris Exposition, it was coated with a thick layer of reddish brown paint and, later, in 1892, with an ochre brown product. In 1899, shortly before the 1900 World’s Fair, it turned yellow: five shades of this colour were applied, from yellow-orange at the base to light yellow at the top. “The fact that these two early repainting campaigns were undertaken less than eleven years apart shows how important it was to Gustave Eiffel that the metal structure be protected, as this was the only way to ensure it could remain standing. Each repainting campaign was an opportunity to experiment with new products and compositions, entrusted to different companies (Société anonyme des gommes nouvelles et vernis in 1889, Georges Hartog & Cie in 1900) in order not only to improve the Tower’s protection, but also to offer a new understanding of this singular building.[1]” In 1907, when the Tower became permanent, Gustave Eiffel opted for the yellow-brown colour bound to cover it for forty-seven years. In 1954, the structure returned to its origins with a brownish-red colour, whereas the bronze-like shade by which it is now known, called “Eiffel Tower Brown”, was chosen in 1968.

How is the Eiffel Tower painted today?

This historical monument’s official website also presents a detailed analysis of the data and procedures involved in its coating process. Here, we summarise the key figures of this monumental intervention work:

- 60 tonnes of paint;

- about 50 painters, all of them specialists in work on metallic structures at great heights and on towers, and completely unaffected by vertigo;

- the weight of eroded paint between two painting campaigns is estimated at 15 tonnes;

- 250,000 m² are repainted;

- 55 kilometres of safety line.

Each campaign is also an opportunity to check the building’s condition in detail and, if necessary, replace any corroded metal parts. The process’ scale and complexity require a rigorous method that includes as follows:

- a preparatory stage to search for the most corroded areas;

- paint stripping of these areas;

- any structural repairs;

- surface cleaning in preparation for the subsequent application phase;

- application of an anti-rust primer;

- second application to strengthen the rust-proofing;

- application of a final coat.

Repainting work in 1924. © Gallica Digital Library

Repainting work in 1924. © Gallica Digital Library

Repainting work in the present day. © AdobeStock

Repainting work in the present day. © AdobeStock

Depending on its complexity, a painting campaign can last, on average, from eighteen months to more than three years (except for the current one, which we will discuss later), with any interruptions being due to the weather, both in winter and summer – considering that it is impossible to paint on a substrate that is too cold and the paint does not adhere well in wet conditions.

Two more interesting facts about the coating phase: painters still work today with the traditional methods used in Gustave Eiffel’s time, applying the paint mainly by hand with Guipon brushes – so much so that, hanging with harnesses from the structure while repainting it, they have become the iconic symbol of this operation. Moreover, three tones characterise the paint used, from the darkest one at the base to the lightest one on the top, to create a visual impression of uniformity when viewed from afar.

The twentieth painting campaign

In 130 years, therefore, the Eiffel Tower has already been repainted 19 times. Its twentieth, complex painting campaign began in 2019. Intended to bring the structure back to the splendour of its early 20th-century golden “dress” for the Paris 2024 Olympics, it is however taking longer than planned due to numerous setbacks. An article by Pierre-Antoine Gatier, the architect in charge of Historical Monuments whose company was entrusted with the management of this latest repainting campaign, states that this intervention “constitutes a new stage in the history of the Eiffel Tower, as we are also planning to strip the previous layers of paint off and to restore the structure itself. This is a major turning point towards a new approach to conservation […] that aims to mitigate the expansive corrosion of ferrous materials. It also relates to an extraordinary cultural history surrounding the choice of colour and the Tower’s place in the larger urban landscape of Paris. The scientific approach implemented in the context of this 20th painting campaign thus integrates an adapted study methodology which combines analyses of historical data with scientific information gathered on site during complementary inspection campaigns. This method has allowed us to produce a detailed analysis of the history of the Eiffel Tower’s painting campaigns, with information on the colours used, their composition, manufacturers, applicators, the reasons for changes in colour, and so on.”

Issues and setbacks of the last campaign

After a nine-month break due to the pandemic, the campaign resumed in January 2022, only to be interrupted again due to the high lead level detected, generated by the removal of the previous 19 layers of paint. As an article in France Bleu stated, “Lead levels around the monument continue to be problematic. The technique called piquage, used to remove rusty layers of paint by collecting them in a large net, slowed down the work. The collection of the oldest paint layers released a large amount of lead.” Lead is a carcinogenic agent, so piquage workers must wear suitable protective masks and take a decontamination shower at the end of each work shift.

The goal of the City of Paris was for the Eiffel Tower to be recoated entirely for the start of the Paris 2024 Olympics, but work is now planned to be suspended for the duration of the competition and only resumed at the end of the Games.

The corrosion of iron: the Dame de Fer is 135 years old, and it shows

In the initial plans, as mentioned, the Eiffel Tower was to stand in the Paris sky for only twenty years: its dismantling should have taken place in 1909, but long before that, despite initial scepticism often translated into outright hostility, the Dame de Fer had already won the hearts, and eyes, of Parisians – and the whole world. Indeed, its dismantling would have solved, albeit drastically, one of the most severe problems afflicting its metal structures: corrosion. Gustave Eiffel himself had stated that ‘identifying and stopping the spread of rust is the biggest challenge to the construction’s longevity” and identified a possible solution in frequent maintenance, suggested to keep the structure in good condition for as long as possible. In particular, some defects that had never surfaced before, such as rust stains and widespread cracks, came to light due to the delays in the last repainting work. This was the situation noted and denounced by workers on strike in February, who were concerned about the structure’s degradation, even visible to the naked eye. The strike, which blocked tourists’ access to one of the most famous monuments, obviously had an international echo that sparked a debate.

Already in a June 2022 article, the weekly publication Marianne provocatively wondered whether, after watching Notre Dame burn, Parisians would witness another catastrophe: the collapse of their symbol, the Eiffel Tower. “According to several confidential reports (three confidential surveys carried out between 2010 and 2016, Ed.),” the article read, “the most famous French monument has been in a very degraded state for several years, and its maintenance leaves much to be desired.” One reported testimony was certainly not reassuring: “In emergency cases (for damaged surfaces, Ed.), on certain areas, a coat of paint is simply applied over existing layers that are flaking off. That is heresy.”

The corrosion of iron rivets on a metal structure similar to the Eiffel Tower. © ipcm / Generated with AI

The corrosion of iron rivets on a metal structure similar to the Eiffel Tower. © ipcm / Generated with AI

Dismantling or repainting?

The problem stressed by many is that the Eiffel Tower would need a complete renovation but is currently undergoing a simple cosmetic makeover in anticipation of this year’s Olympics. The cost of this campaign, during which one-third of the monument would have had to be dismantled to apply two new layers of paint, amounts to 60 million Euros. However, the unforeseen events we mentioned have meant that only 3% of the construction is going to be repainted before the major sporting event that will turn the world’s cameras towards Paris.

According to the Guardian, “The company that oversees the Tower, SETE, which is 99%-owned by the city hall, is reluctant to close it for a long period because of the tourist revenue that would be lost. The Tower receives about 6 million visitors in a typical year, making it the fourth most visited cultural site in France after Disneyland, the Louvre, and the Palace of Versailles. Its Covid-enforced closure in 2020 led to a loss of €52m in income.” The British newspaper continued this analysis by pointing out that in a 2014 report, expert paint company Expiris found the Tower had cracks and rusting, and only 10% of the newer paint on the Tower was adhering to the structure. “Even if the general state of the anti-corrosion protection seems good to the eye, this can be misleading. [...] It cannot be envisaged to plan for a new application of a coat of paint that will do nothing but increase the risk of a total loss of adhesion in the system.” A third report in 2016 found 884 faults, including 68 that were said to pose a risk to “the durability” of the structure. According to many experts, therefore, the current repainting campaign would be a palliative, whereas the Tower would need a far more radical intervention to protect it from the wear and tear of time.

Architect, engineer, and historian Bertrand Lemoine, however, is more optimistic: according to him, “the enemy of iron is corrosion, caused by water and air that gradually oxidise iron exposed to open air”, but “if it is repainted, the Eiffel Tower can last forever”. The same opinion is held by Kako Naït Ali, a materials engineer and corrosion specialist, who explained in an interview that corrosion is the natural degradation of iron, but there is nothing dramatic about it. “We should be vigilant in areas where it has a structural impact. The areas where rust is most visible are not necessarily those where its presence is the most problematic: between rivets, for example, it is not visible. If corrosion were to affect the area of a rivet, the resulting deformations could create gaps and allow air and water to pass through, further exacerbating the problem.” At the same time, Naït Ali emphasises that the monument cannot be left in this state. “If we wanted to keep it as long as possible, we would have to disassemble and repaint it completely. The building is covered with 3 mm of paint: the 19 layers applied over one another since its construction. In many areas, old paint and corrosion traces are removed manually before applying the new coating layer. It is the resulting irregularity of the substrate that produces the marbling-like visual appearance under the paint. It is not ideal for sustainability, either,” said the expert.

The future of the Iron Lady

The photos of the Dame de Fer’s corroded parts taken and posted by striking workers and visitors went around the web, raising alarmed and concerned reactions. However, those responsible for the twentieth painting campaign reassured the success of this latest intervention, explaining its related difficulties in an interview with franceinfo. “This is the first time we have dismantled the Tower. It is an incredible success to have been able to realise this project,” emphasised Pierre-Antoine Gatier, referring to this technological feat. The dismantling work was all the more difficult as it was necessary to deal with the lead in the Tower’s coating: “We had to reinvent all the implemented techniques, redefine all work protocols. This was expensive,” explained the architect. He then added, “After the paint stripping operation carried out at the end of the pandemic, the iron we brought back to the surface is in an exceptional state of preservation. As for corrosion, it is strictly superficial and does not call into question the solidity of the iron parts.” Magazine Marianne’s article also mentioned the existence of 68 parts subjected to reporting out of a total of over 18,000 pieces. However, Gatier replied that, “These are secondary elements. There is no urgency regarding these repairs.”

The franceinfo article also quotes Bernard Giovanonni, SETE’s technical advisor from 2009 to 2016, who drew up the three reports mentioned by Marianne at the company’s request. “We are lucky: the Eiffel Tower is made of puddle iron, a material on which corrosion is less aggressive. The main structure of the Eiffel Tower endures.”

The percentage of the Tower repainted to date is 60% and includes “the outer faces of the four pillars, the decorative arches, and almost the entire spire,” SETE told franceinfo. Pierre-Antoine Gatier hopes to “finish painting all the exterior faces of the Tower” by the start of the Olympic Games. Afterwards, the work is scheduled to resume to paint the lower interior faces, the parts where the coating is most damaged, in 2025-2026. According to SETE, the twenty-first painting campaign, scheduled for after 2026, will include a new paint stripping phase, particularly on the decorative arch between the south and west pillars.

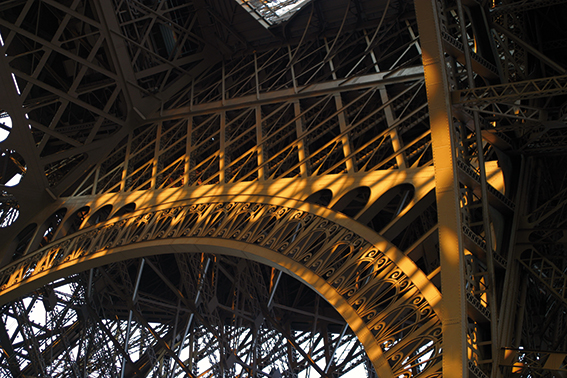

The Eiffel Tower is currently undergoing its twentieth repainting campaign. © AdobeStock

The Eiffel Tower is currently undergoing its twentieth repainting campaign. © AdobeStock

Impossible to imagine the Paris skyline without the silhouette of its iconic iron symbol. © AdobeStock

Impossible to imagine the Paris skyline without the silhouette of its iconic iron symbol. © AdobeStock

In the pages of our Corrosion Protection magazine, we have repeatedly emphasised the consequences of corrosion and the high costs involved in restoring damaged structures. The circumstances we have described by quoting some concerned testimonies from French and international media indicate that a forward-looking, effective intervention strategy is needed for the Eiffel Tower. It is impossible to think of Paris, and France, without this old Lady – with strong bones but weak armour – and without what it has been representing throughout its long history as the symbol of modern and industrial engineering in the transition between the 19th

and 20th centuries.

[1] P.-A. Gatier, “La Tour Eiffel, une histoire de couleur” in “La Tour Eiffel sous toutes ses couleurs”, La lettre de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts numéro 95, pp. 28-33.